1. Introduction: Beyond the Textbook Model of GFR

As clinicians, our understanding of renal physiology is foundational. However, the classic textbook model of glomerular filtration, while useful, often oversimplifies the complex processes that govern kidney health. This whitepaper revisits these core principles through the lens of modern biomarkers, providing a more nuanced framework for interpreting diagnostic results and enabling earlier, more confident clinical intervention.

2. The Creatinine Story: A Respected but Flawed Legacy Marker

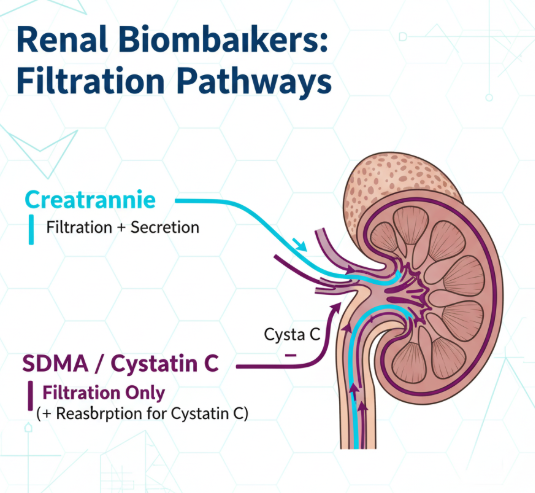

For decades, serum creatinine has been the cornerstone of renal function assessment. Its utility is based on its relatively stable production rate from muscle metabolism and its primary clearance by the kidneys. However, its diagnostic accuracy is limited by several well-documented physiological factors, including significant influence by patient muscle mass, the need for a 50-75% loss of GFR before levels rise above the reference interval, and variable rates of tubular secretion. Understanding these limitations is the first step toward a more sensitive diagnostic strategy.

3. The Physiology of Modern Biomarkers: A Clearer Signal

The limitations of creatinine have driven the validation of biomarkers that provide a more direct and less confounded assessment of GFR.

Symmetric Dimethylarginine (SDMA): Produced by all nucleated cells during protein methylation, SDMA is a small molecule released into circulation. Its clinical power lies in the fact that it is almost exclusively eliminated from the body by glomerular filtration and is not significantly impacted by muscle mass, making it a more sensitive and reliable indicator of early GFR decline.

Cystatin C: This low molecular weight protein is also produced at a constant rate by all nucleated cells. It is freely filtered by the glomerulus and then fully reabsorbed and catabolized by the proximal tubular cells. A decrease in GFR leads to its accumulation in the blood, making it another excellent marker for early detection of renal dysfunction.

4. The Role of Proteinuria: Assessing Glomerular Health

While GFR markers assess filtration capacity, the urine protein:creatinine (UPC) ratio provides a direct window into the health of the glomerular barrier and tubular function. Persistent proteinuria is a key indicator of renal damage, often preceding changes in GFR markers. Integrating UPC assessment is therefore critical for a complete picture of renal health.

5. Conclusion: A Synthesized Approach to Renal Assessment

A modern, proactive approach to renal health requires moving beyond a single data point. By understanding the unique physiological story told by each biomarker—Creatinine, SDMA, Cystatin C, and UPC—the clinician can construct a far more detailed and accurate picture of a patient's kidney function. This deeper understanding is the true pathway to earlier diagnosis, more effective management, and improved patient outcomes.

Summary of Key Renal Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Primary Source | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | Muscle Metabolism | Widely available, inexpensive | Affected by muscle mass, late indicator |

| SDMA | Protein Methylation | Not affected by muscle mass, early indicator | Newer marker, requires specific assays |

| Cystatin C | All Nucleated Cells | Not affected by muscle mass, early indicator | Can be affected by severe inflammation |

| UPC Ratio | Plasma Proteins | Direct measure of glomerular/tubular damage | Not a direct measure of GFR |